05.11.2014

NIGHTMARES

When I was studying at art school part of the course was art history.

One red-haired lecturer had the job of teaching us about modern art, and she loved provoking us with how extreme it could be. (And how extremely far from what our young minds thought art should be.) One day, she told us about Rudolf Schwarzkogler. This Austrian performance artist had, at some point in the 1970s, in front of an audience, put his penis on a wooden board, and carefully cut it into thin slices. As you might cut a salami. She didn't show us any images, but she didn't need to.

I barely slept that night. I can remember being quite desperate trying to flush the mental pictures out of my head. I must have somehow succeeded in sublimating the story, I finished the course, even attending further lectures by the red-haired sadist. I do remember I was extremely careful never to stray into the part of the building used by performance artists.

But I was left kind of fascinated by the vulnerability of the body, the idea that one could wilfully, irreversibly demonstrate one's own mortality. We can all get horrified and fascinated by something gory. I am sure you have been stuck in a queue on the motorway, only to find its cause is everyone slowing to a crawl to rubberneck a crashed car. And zombie films, what are they but us choosing to expose ourselves to the body being disassembled.

When you live a life making creative work, the issue of commitment is there with every piece of work. How much do you commit to each piece of work you do? Alan Fletcher used to talk of two kinds of artist, the chicken and the pig. He said "when it comes to breakfast, the chicken walks away having given an egg, whereas the pig is completely committed".

As I began my design career, Rudolf Schwarzkogler came back to haunt me. How could an artist commit so much to a creative act? He was surely the king of pigs. Back in the 1980s it was difficult to verify a story like Schwarzkogler's. I looked in lots of art books, without ever seeing his name. No artist I met had ever heard of him. There was no Google. Over time, Schwarzkogler became a fainter and fainter memory.

The other day I came across the story of Japanese artist Mao Sugiyama, who had sent this tweet (originally in Japanese): "Please retweet. I am offering my male genitals (full penis, testes, scrotum) as a meal for 100,000 yen [about £850]. I'm Japanese. The organs were surgically removed at age 22. I was tested to be free of venereal diseases. The organs were of normal function. I was not receiving female hormone treatment. The length at full erection was 16.1 cm [just over 6 inches]. First interested buyer will get them, or I will also consider selling to a group. Will prepare and cook as the buyer requests, at his chosen location. If you have questions, please contact me by DM or e-mail."

In April of this year, in an art event, Sugiyama served a meal to five paying customers in Suginami ward in Tokyo, the genitals braised, and garnished with mushrooms and parsley. The district mayor, Ryo Tanaka, said: "many residents of Suginami and elsewhere have expressed a sense of discomfort and feeling of apprehension over this", and reported Sugiyama to the police. But apparently there is no specific law in Japan against cannibalism, and so no charge to answer. The diners remarked that the genitals were rubbery and bland, which must be disappointing for Sugiyama, its not as if he can learn from his mistake and serve the meal again with less cooking and more seasoning. The genitals had been frozen, which inevitably spoils the quality of sweet meats as it does squid or any delicate flesh full of air pockets. I notice from the news articles that Sugiyama has also had his nipples removed. Not enough for a follow-up meal, but an hors d'oeuvre perhaps, salted and popped on top of squares of brioche?

Sugiyama in chef hat, literally serves himself (via whatonjinan.com)

Sugiyama in chef hat, literally serves himself (via whatonjinan.com)

Sugiyama, now bereft of all signs of gender, doesn't want to associate with either sex. He intends to wear only transparent clothes, to show us the nothing that remains.

Encountering this story spurred me to reach back into my past, and give flesh to the myth of Schwarzkogler.

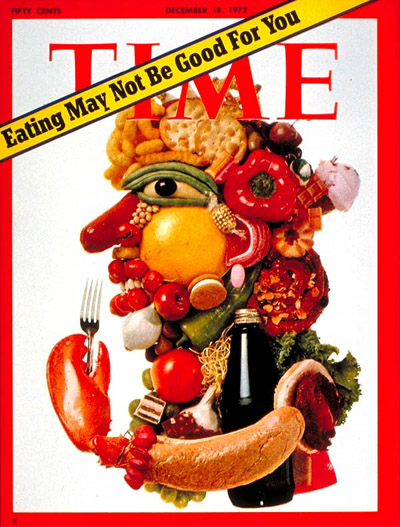

Quickly I found this: "Chris Burden once remarked that a 1970s Newsweek Magazine article, which had mentioned himself and Schwarzkogler, had embarrassingly misreported that Schwarzkogler had died by slicing off his penis during a performance." The article was apparently by the usually reliable Robert Hughes, titled The Decline and Fall of the Avant-Garde, in TIME magazine no less. The cover of the issue in which Hughes' essay appeared, 18 December 1972, is apposite given what I am writing about - dismemberment and cannibalism. In the essay, Hughes wrote that Schwarzkogler "proceeded, inch by inch, to amputate his own penis, while a photographer recorded the act as an art event". And Hughes wrote that Schwarzkogler had killed himself through "self-amputation".

Could it be true that the source of such vivid nightmares was untrue?

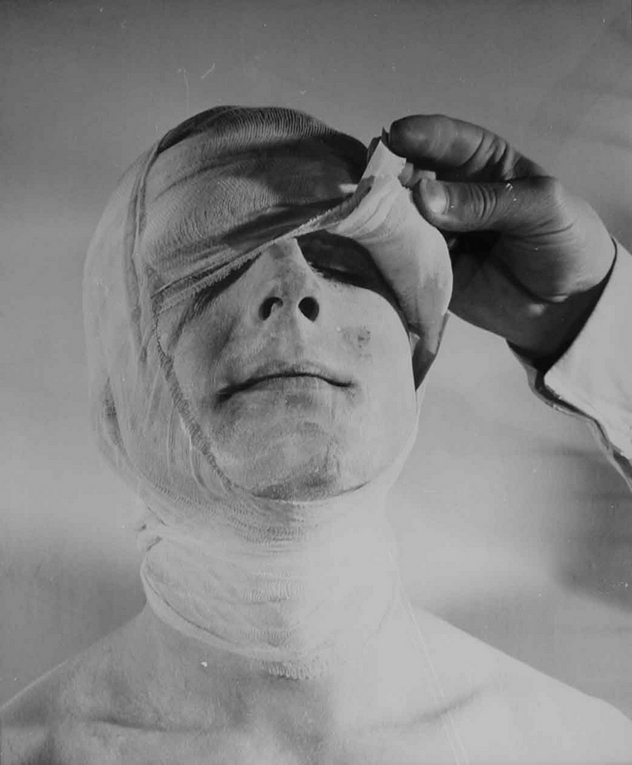

In fact, it seems that the photographs that tricked Hughes were of Schwarzkogler's friend Hans Cibulka, taken in 1965 by Schwarzkogler, they show Cibulka cropped off at the neck, posing with his penis wrapped in a bandage ready to be cut, and then actually cutting a roll of animal flesh. The kind of trick of association used for centuries by magicians, and now by cinema. It is a testament to the evocative power of 70s Teutonic performance art: Schwarzkogler wanted to make it seem as though a man was self-mutilating, and obviously managed exactly this. Hughes fell into some kind of trap, taking tromp l'oeil for the real thing, not checking, not feeling he needed to check, not caring if it was true or not, it was depraved anyway. He manufactured a nightmare from he was most afraid of - creativity turned upside-down to become degradation. And he passed that nightmare on.

One of Schwarzkogler's milder photographs (via imkinsky.com, brace yourself for the photos that dismayed Hughes)

One of Schwarzkogler's milder photographs (via imkinsky.com, brace yourself for the photos that dismayed Hughes)

We might not be attracted to Schwarzkogler's art, but it was a fierce time, rife with extreme politics, and it was this perhaps dictated to some young Germans and Austrian artists that they needed to create art to match it. There is a sensitive essay about Schwarzkogler here. Hughes was also wrong about Schwarzkogler's death too. He fell out of a window.

So I had been misled by someone who was misled. Hughes' fallacies had found their way into the classroom, and into my impressionable young head.

It got me thinking about other nightmares from my youth which had stemmed from misprision or even wilful distortion on the part of the storyteller.

Perhaps the 1970s was a spectacularly bleak decade. It was certainly made to seem so. I remember a history teacher telling us that it almost didn't matter whether we learned or not, that Marxism was going to thrust Britain into a new Dark Ages. I remember a music teacher spending an entire lesson railing against John Cage's composition called 4'33", saying that all modern musicians were nihilists and music was dead. Cage's composition consists of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. Our teacher was fairly frothing at the mouth over literally nothing, most especially at the exactness of the four minutes and thirty-three seconds that this nothing lasted. I remember a policeman visiting the school and showing us how to hide under a table when the Russian nuclear missiles started to rain down. I remember programmes on television showing us that a new ice age was unavoidable and imminent, it was going to entomb and freeze us all, the ice caps were demonstrably growing, the screen full of cliffs of ice advancing, creaking and cracking.

I was told, with certainty, that I would be living in an ice-bound post-nuclear Marxist state. With music only silence, and art only self-amputation. One way or another, physically or spiritually, I would be dead. None of this has, or will come to pass. People with the highest qualifications and the greatest authority were busy getting facts wrong and interpretations of those facts woefully far of what has come to be. And sending me to bed with almost unmanageable visions of the end-of-times. There is a catalogue of prophesied apocalypses by Matt Ridley; the population explosion, global famine, flu epidemics, water wars, oil exhaustion, falling sperm counts, thinning ozone, acidifying rain, nuclear winter, killer bees, mobile phone brain cancer. And tunnelling North Koreans popping up in America? The YSK bug, remember that? And just last year, the Large Hadron Collider bound to create a black hole and destroy the whole planet? Those too ready to tell such terrible tales Matt Ridley accuses of 'apocaholism'.

Worse than getting facts wrong, it seems these people who spooked me feared the wrong things. The things they feared were cul-de-sacs were in fact new avenues. The point of John Cage's 4'3" is that during it you can hear all sorts of sounds, not music but coughing, machinery, rustling, birdsong, ambient sound. Cage said the purpose of the piece was "to make people listen". And this revelation turned out to be the beginning of a great aural revolution. The idea that ordinary sound can be 'music' has inspired Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Philip Glass, Brian Eno and by extension feeds into pretty much every field and piece of modern music. Our political system resisted Marxism, and (much as it might amaze us) acted as an alternative attractive enough to cause Marxism to be overthrown throughout the Communist Block. You can argue that Schwarzkogler is a descendent of Hughes' much loved artist, Goya. Hughes loved Goya for his political engagement, depicting "a world of moral chaos". Goya was working in the 1800s responding to the ravages of Napoleon, Schwarzkogler in the 1970s responding to the ravages of Marxism. Hughes prefers his gore depicted by alizarin crimson rather than fish blood, but the essential subject matter, the individual torn asunder, is the same. Rather than the end of something, Schwarzkogler was a beginning. All artists today owe a great debt to Schwarzkogler and his ilk, and many use his techniques; the body as a canvas, photography and shock.

Nightmares beget nightmares. There are experts telling apocalyptic stories today, the horsemen have different names from the ones that trotted out in the 1970s, today it's Money and Islamism, CO2 and Piracy. But we must not be too hard on what Gore Vidal called the "experts". Visions of the Apocalypse exist in every age. They are a form of rhetoric. A presentational gambit. They wrest us away from complacency. Make the message urgent. Beyond urgent. Necessary. Absolute.

But does the absolute exist? The universe and everything in it is more about the contingent than the absolute, everywhere we care to look, in science, in culture, things are fluid and interdependent. Pretty much nothing happens without needing lots of other things to also happen, and often what happens isn't what anyone could foresee. Our mistake is to take them, the "experts" or the visions, too seriously.

What have I learned? What has the lesson of Schwarzkogler fallacy taught me? Like Sugiyama's guests: the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

Quentin Newark